Why do girls choose computing?

01 July 2020

Katharine Childs and Dan Fisher explore how young people make choices to learn about computing at clubs and in classrooms, and how these choices differ between boys and girls.

The current gender imbalance in schools and workplaces shows that many girls are not choosing computing. Yet there is one area of computing where girls have better representation which is closer to achieving a balance: non-formal learning activities, such as after-school or weekend clubs. A variety of different programmes offer coding clubs to young people, and these extracurricular activities consistently see a higher proportion of girls taking part. In 2017, 33% of the young people attending CoderDojos were female. In a 2018 survey of Code Clubs, the proportion of girls was even higher at 40%. Yet GCSE data from 2017 showed that only 20% of students who chose to study computer science were female, and the subject remains one of those with the greatest gender imbalances. Why are girls better represented in non-formal learning than in formal learning? And how might this interest be transferred from the club to the classroom?

Gender differences when making choices

Non-formal learning and formal qualifications in computing both have one thing in common: they are optional learning activities. Young people choose extracurricular activities based on factors such as the location and time of the clubs, and their interest in the subject matter. When making GCSE choices, teenagers evaluate their subject options based on different factors. I spoke to Maddie, aged 17, who described the competition which existed amongst STEM subjects at her secondary school when young people were asked to choose their options. “If we were doing triple science, we couldn’t do computer science as well because there wasn’t room in the timetable,” she explained. At Maddie’s school, the subject was only recommended to students who had performed well in maths, where a gender imbalance also existed. “There were 25 of us in our further maths group, but only 8 of us were girls,” Maddie recalled.

As well as practical considerations, young people also take into account longer-term factors, such as their expected success in the subject or their career aspirations. The influence of gender norms on career aspirations is another reason why girls may not choose computing. Up until the last fifty years, girls were encouraged to base their life choices on their potential for marriage and being a good homemaker. Girls are still heavily influenced by the weight of societal expectations that can prevent them from choosing by interest and engagement in favour of subjects which are traditionally seen as ‘for girls’.

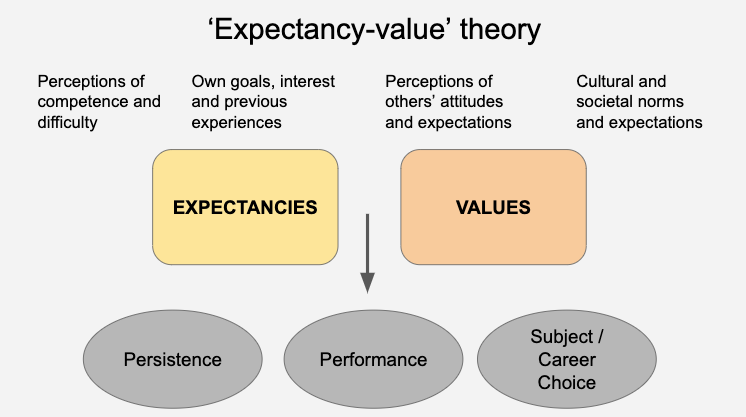

However, making decisions can be complex. Whether girls choose to study computing formally or informally cannot be distilled down to a single influence. A model called expectancy-value theory is helpful to explain how young people may make decisions about computing.

Expectancy-value theory identifies that learning choices are motivated by a student’s perceived expectation of success in a subject, which then influences their judgement of the subject’s value. Research has shown a correlation between these two factors: young people tend to value the subjects where they feel competent, and young people who value subjects are more likely to choose them.

So what role can non-formal learning play in developing positive attitudes towards computing? A recent study asked adult instructors about their perceived differences between girls and boys at their coding clubs. Although the responses may have been biased by general gender perceptions, there was a tendency to view girls as more persistent than boys in their perseverance towards reaching an end goal, yet less confident in their own ability to achieve that goal. This suggests an internal struggle where girls are determined to do well in computing, yet lack the confidence to believe that they can. When this struggle takes place in formal learning choices, girls’ lack of confidence about computing can impact the value that they place on the subject, which may mean that they are less likely to choose it.

Non-formal learning clubs create liminal spaces that redefine success

Non-formal computing activities like Code Clubs enable the learning of computing concepts in a free-form and nurturing environment. It is a space where girls are less likely to be negatively influenced by daily societal pressures.

The clubs can be seen as “liminal spaces”, a term coined by the anthropologist Victor Turner to describe how, during rituals and rites of passage, people are given permission to transition from one state to another. For example, a child becomes part of a school community while on a trip to buy their first school uniform. Turner was particularly interested in the middle phase of these rituals, which he said possessed the power to transform through the ambiguity that occurs.

Non-formal clubs are set up to be spaces where girls can take advantage of this ambiguity. They aren’t just asked to follow instructions and work towards learning a curriculum; they are given the right conditions to make computing projects that are fun, interesting, and meaningful to them.

The rules around attainment can also change. Non-formal clubs offer learning opportunities without summative assessment, and unlock girls from the expectation that their achievement is defined by a numerical grade. Instead, attainment can be achieved with a project that meets their goals, develops new skills, and is received well by peers.

Non-formal learning opportunities for young people in computing

The current global pandemic has provided challenges and opportunities to evaluate delivery mechanisms for effective learning. This is a great time to look into creating new spaces for liminal, non-formal learning for young people that may in turn drive their formal learning choices. Here are some suggested resources:

- Digital Making at Home is a set of free, weekly video tutorials from the Raspberry Pi Foundation

- Learn Computer Science at Home contains free resources with age-appropriate signposting designed by code.org

- Apps for Good Home Learning have created new courses that can be accessed for free, which focus on creating apps and machine learningThere are free, short courses available called Prepare to Run a Code Club and Start a CoderDojo to take the first steps in leading a non-formal learning space